Stacey Parks, my wife, has taken a space in Cambridge on Bow Street. It has large windows and looks out at the Lampoon Building at Harvard. She plans to open a space for art. An art space. I've been involved in a few since I was a boy on Via Margutta in Rome, and I suspect things have changed a lot since I ran my last gallery on Newbury Street ten years ago. It was called Gallery 28 and it was just across the street from the Ritz. It wasn't really a gallery, but an art school exhibition space that showed the work of artists from Boston and New York for the most part. Occasionally it included faculty in the shows, which was nice for the school.

I guess what I'm getting at is that exhibition spaces like the ones I've shown in or directed have long been absorbed into our ever-widening consumer culture. Alternative spaces are an anachronism. Part cliche, part joke. Everyone is excited that she is doing this space, but sometimes the reaction is all about business. Will it succeed? How will you pay the rent? Cambridge is not a good place to try to sell art. It never occurred to Stacey that she would be selling art, just showing it. I remember when I opened my second "alternative space" in Providence, RI(The Cleveland Gallery), and I jokingly told the Providence Journal art critic in an interview that if I ever sold a piece it would be like Christmas. That was the headline, of course. What I was suggesting was that it would only come once a year. My assistant did sell some pieces while I was out.

Even in Provincetown, on whose outskirts we spend our summers, everything is commerce. I was approached several times by one of the more prominent spaces about either partnering or taking over entirely. The talk was always about selling. Now don't get me wrong, I understand that an artist needs to sell his or her work, maybe, but art is not about commerce. That aspect to art, if it has such an aspect, just NEVER interested me, and I was poor most of my life. Professionalism in the arts is almost oxymoronic, and even embarrassing, but it is the norm in New England. It is anathema and even considered naive to think of art in non-commercial terms.

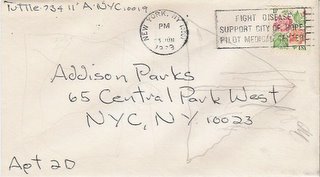

Yankees are nothing if not practical, and it is not practical to think of art in non-professional terms. Amateurism is rank. Of course I couldn't disagree more. But no one makes art for the love of it, or even the fun of it anymore, and what good is that? (I was just speaking with my friend and rare book dealer John Wronoski about this very subject yesterday, about art made by writers and writing done by artists, and how much more interesting that can be--and this will be the real subject of this or the next posting). We get something akin to a coffee cup now. Shoes. Newbury Street in Boston is all about hair and shoes, and that is Boston. A friend of mine, Martin Mugar, was reviewed in the arts section of the Boston Globe today. On the front of the section was a big spread about beads. A picture the size of a bus. His work was blurbed in the back with a postage stamp for an image. This is a world class artist. So it goes. The blurb funnily enough reduced the work to just that, fun, but in a demeaning way. As though Jackson Pollock was so fun with all those squiggles. Embarrassing. But such is Boston. Which is why Stacey is opening a space in Cambridge. Maybe some Europeans will wander by and understand. Art for art's sake in America. How refreshing. That was what her landlady said, and she is French, naturally.